[Below is the modified version of the newspaper column assignment submitted by Priscilla Ng, a student in the inaugural “History of Hong Kong” class offered in the winter term of 2016. All rights reserved.]

Thursday, 18 October 1956

Todd’s Two-Cents: Rage behind the Riot

Todd’s Two-Cents returns this Thursday with a commentary and analysis on the rage behind the recent uprising in Kowloon area, where around two hundred were killed or injured (Wah Kiu Yat Po, “Two Hospitals in Service, refrain from visiting today”). The colonial government’s official statement on the riot dodges the sensitive boundaries of governance in Hong Kong and exemplifies its negligence towards the people’s well-being, as Todd reveals a conspiracy within its words of authority.

We have failed to perceive our own crookedness.

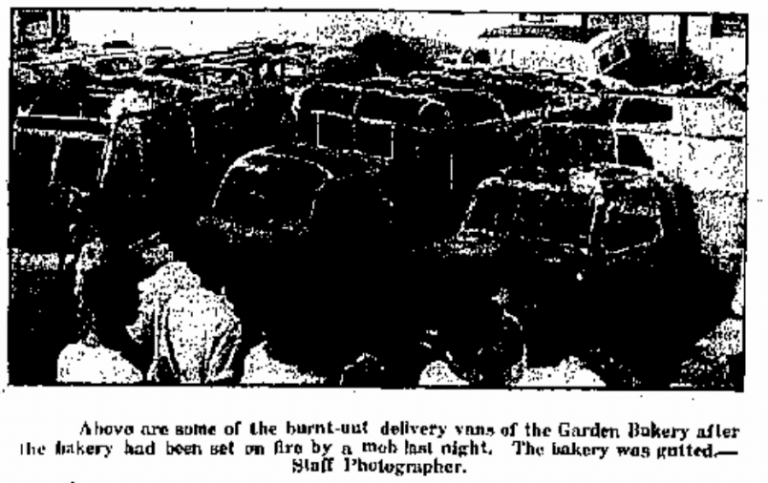

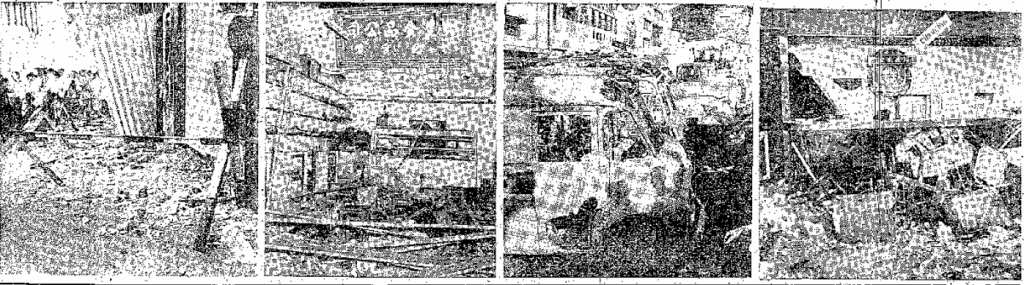

Blood shed, houses burned, Kowloon in ruins. The city wonders what will come next after The China Mail had reported last Saturday (the 13th) that the police have rounded up and seized over three-hundred suspects from the riot in Kowloon, sending them promptly to the Chatham Road Concentration Camp (p. 1). The sudden outburst of violence on Double-Ten Day prompts inevitably a plethora of voices in analysis of the present nationwide political factions, attributing the atrocious bloodshed to the low wages, long working hours, and overcrowded living conditions of the Hong Kong people. As cars were burned down and nearby civilians looted mercilessly, Castle Peak Road in the Sham Shui Po area suffers from the remains of burning buildings and Communist angst.

You are hereby invited, dear reader, to perceive this violent eruption as a warning from the people, in their own unique mannerisms that belong to a class of labour and life. The atrocities that have occurred during the past few days are an opportunity for us to evaluate, because as the old proverb reads: “the crooked stick will have a crooked shadow.” Consider and mull over our crookedness by traversing back to the deadly Christmas Eve merely three years ago, when some seventy-thousand civilians were displaced from the Shek Kip Mei Estate due to a fatal fire (Ta Kung Pao, 26 December 1953, p. 4). Questions were raised regarding the city’s problematic housing circumstances: to what extent is the government willing to go to compromise the safety and well-being of civilians, the class that contributes the bulk of production, labour, and economic development? With the citizenry’s increasing awareness of their own social standpoints, propaganda can only do so much to drown the poisonous, mutinous, and rebellious thoughts of the people – thoughts out of pure desperation and hunger for survival.

Let us observe how the colonial government explains this occurrence.

Ta Kung Pao labels the government’s actions in response to the riot as an attempt to shift blames and point fingers, crediting the Chinese political disputes up north as the motivator behind the violence (Ta Kung Pao, 14 October 1956, p. 1). A well-played and rather convincing cover-up for the truest issues that need to be considered with haste. Rebellious actions as such had occurred in the past, namely the general strike of 1925–1926, in which one of the main motives behind the rebellious act was a demand for “rent reduction” and “freedom of residence” (Deng Zhongxia, Zhongguo zhi gong yun dong shi, 1919–1926). History seems to repeat itself.

More significant issues that affect each and every household in Hong Kong should be addressed, and the Double-Ten Day riot serves as a part-opportunity, part-warning to the government and the people to consider these issues in a solemn manner, and act with efficiency. One of them is housing in Hong Kong—the dreaded topic that nobody wants to tackle, but also the deadliest of all. Governor Alexander Grantham describes urban housing as Hong Kong’s “greatest social problem,” acknowledging that the “influx of a neighbouring country” with thousands of people waiting to move into proper housing, where the demand is disproportionately higher than the supply, makes Hong Kong’s housing concern an exceptional one (Alexander Grantham, “Social policy—Address by the Governor,” Hong Kong Hansard, session 1954, p. 20–21). The number of people that need to be housed reaches a whopping 350,000 (p. 20–21). Another address from Governor Grantham explicitly proposes an excuse for intervention, following promptly the deadly fire at Shek Kip Mei Estate in 1953. An estimated “$16 million from Government funds” was needed for site clearing, reconstruction, and the re-assimilation of the affected households and mass (Alexander Grantham, “Excuse for intervention,” Hong Kong Hansard, session 1953, p. 354–355).

Thus, the Hong Kong Housing Authority was born, created as part of the resettlement policy after the Shek Kip Mei fire in order to develop low-cost housing that will benefit the lower and working class in the long run. The governor does highlight the difficulty of formulating a solution to Hong Kong’s housing problem, recognizing that it is a pressing one, as well as a costly one (p. 20–21). With the recent occurring of the Shek Kip Mei incident and the ongoing pressures in housing and surging immigrant numbers, it is rational to attribute the inescapable demand for proper housing as one of the crucial motives behind the angry outburst of the Hong Kong people on the 10th of October.

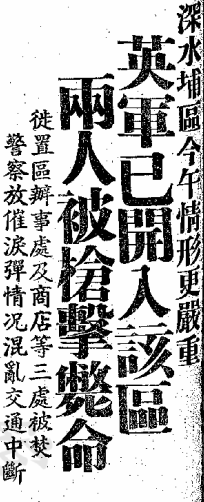

Situation in the Sham Shui Po area worsens; English army enters the area, two people shot. Source: Kung Sheung Evening News (11 October 1956, p. 1)

Poor living conditions and inadequate healthcare services provided to the lower and working classes are other pressing matters that beckon the government’s immediate attention and action. One extremely relevant example that The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong raises in their fifth annual report specifies the average monthly salary of clinic attendees (wives of Service personnel) to be $136.02. However, it had also acknowledged the fact that this figure “does not give a clear picture of the extreme poverty of many of the patients who attend clinics on account of the fact a number of women from higher wage groups make use of the facility offered” (The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong, Fifth Annual Report, 1955, p. 9–10). According the 1950–51 annual report, “a whole family of five to six may have only a curtained-off cubicle enclosing an area of perhaps no more than 64 square feet,” with no windows, communal hygiene facilities, and unstable water supply (Hong Kong Annual Reports 1950–51, p. 43). Limited health measures and programs are in service to the lower and working classes, even though there is an undeniable demand for the establishment of more general hospitals across the city.

The Double-Ten riot thus acts as a window into the minds of the citizens. The efforts of the colonial government in attributing the violence as purely a part of the larger Chinese political struggle detaches itself from the sufferings and the cries of the people. It had, mercilessly, drawn the curtains to this sealed-shut window in hopes of suppressing and drowning out the frantic voices of opposition and rebellion, as well as disregarding the truest matters in our society today. To restate the opinions of many journalists and intellects today, the Double-Ten riot was not exclusively a product of the nationalist-communist conflict that had eventually spread from the north. It bears an immense connection to the ongoing discontent and hardships of the people, and a collective sense of confusion in the Hong Kong strive to survive.

Daniel Todd is a Canadian writer and teacher who has published award-winning novellas in the philosophical sci-fi genre and non-fiction works on human rights. He joined The South China Morning Post in 1952 as a news reporter, and ventured further into journalism as a social columnist.

[Bibliography withheld]